150 years since it was published, our strange fascination with Alice in Wonderland grows ever stronger and ever more curious. Here are 7 explanations why.

Alice in Wonderland is insanely popular. Two books penned by mathematician Charles Dodgson are reportedly the most-quoted works outside of the Shakespeare’s and the Bible. Our culture is filled with Alice: hundreds of adaptions, including Tim Burton’s Alice Through the Looking Glass which comes out next year, huge quantities of fan fiction, numerous blogs devoted to the novel, Mad-Hatter-themed tea parties everywhere you turn, and even a Marc Jacobs’ Alice in Wonderland clothing collection just announced.

And it’s not like it’s deemed childish or quirky: the Royal Mail just released a set of Alice stamps, the British Library is currently holding an Alice exhibition and there was not one but two Alice-themed gardens at the Hampton Court Flower show. Add that to the literary world’s seal of approval and you get No. 18 on The Guardian’s list of 100 Best Novels.

Alice in Wonderland artwork is everywhere, from manga to watercolours to papercut art

Yet it’s a curious phenomenon to have so invaded our popular imagination for exactly 150 years now (the first edition was published July 1865). Action, romance and linear-plotting are all limited – at least in the original books – and the inclusion of these elements in a number of its adaptations displays just how necessary they usually are.

What’s more, the appeal of weirdness is frequently only fleeting: just think of all those strange internet memes that were over-clicked and then forgotten. Arguably the appeal of wackiness is inherently short-lived, because its appeal is based on being new. Unusual. Different from anything that has come before. So how has Lewis Carroll’s particular brand of weirdness remained popular for one and a half centuries? Here are 7 theories why…

Alice in Wonderland stamp, image courtesy of Royal Mail

1. Love for Alice

“Lewis Carroll made this figure — a gutsy kid who’s curious and wants to move ahead to the next adventure… At the time, she seemed to represent something new in children’s literature, a sense of self-sufficiency.”

James Kincaid, Professor of English at USC

What seven-year-old girl, separated from her family and taken to a disturbingly strange alternate reality, never once calls on her parents for help? The success of plucky child heroes is evident in their seemingly-constant presence in successful books since Alice: Harry Potter, Lyra Belacqua, the Pevensie children, the Baudelaire children – all have their parents removed early in their stories. The dearth of parental figures in children’s and YA literature is understandable – it allows the author to raise the stakes far higher and makes the character much more gripping as an active mover-and-shaker rather than a passive victim.

And yet this clearly cannot alone explain Alice in Wonderland‘s popularity. Alice might have been a radical break “At the time” (although the young Jane Eyre was similarly strong-willed and that book was published 18 years earlier) but, clearly, plucky child heroes are no longer unusual.

To the caterpillar’s recurring question “WHO are you?”, Alice replies, “I-I-I hardly know, sir”

What’s more, Alice is a girl of shifting identity who finds it very difficult to define herself – and thus very difficult for us to define her. Tim Burton referred to the Alice from the books as a “very annoying odd little girl” and replaced her with a very different, significantly older, character (played by Mia Wasikowska). That such a switch could be made and the essence remain the same makes evident: it is not simply the girl who we are fascinated by, but the rabbit hole and what’s beneath it.

Mia Wasikowska as Alice We can all picture Alice, but could you describe her personality?

2. mucking about with language

“Gallumphing: the present participle of gallumph”

Wikidictionary, definition of “gallumphing”

In The Jabberwocky, Carroll uses the same rule-breaking yet logical approach to language that forms slang. It even resembles Buffy-speak – “slayage” and “burbled” are remarkably similar in construction, with an unexpected suffix added to an uncommon word (burble apparently dates back to Middle English). The reinforcing power in groups of having a tribal dialect is well-noted by academics, and by anyone who’s tried to seem cool / rich / intelligent / indie by knowing the right lingo.

But it extends beyond this: forming language is a type of self-expression. The ability to create a word that describes what you mean to say more than a real word could is thrilling. It allows us to claim language for our own. It makes language make sense.

Take “gallumphing”. Whether or not we actively think through which words it is playing on (“galloping” “thumping” “triumph” etc), it simply sounds right. You have a sense of it before you interrogate its meaning. From all the times we’ve had to figure out words from parts we recognise, we combine the meanings subconsciously before we’ve worked it through on a conscious level. It reminds me of T.S. Eliot and his seemingly-hapdash melding of speech, slang and allusion. It’s extremely memorable, eminently quotable and delightfully onomatopoeic.

3. Out of copyright since 1907

For novels like Harry Potter, all that fan interest and imagination goes into ‘wrock’ music, next generation fanfiction, short films of Dumbledore’s younger years, buying fake horcruxes online, dressing up in Hogwarts robes, whispering the name of a man without a nose, et cetera. For Alice fans, the same devotion and creativity generates legitimate spinoffs and illustrations, which are both publically available and profit-making, thus receiving more money and attention to produce quality content.

Copyright for Alice expired in early 1907 – by December that year, 7 new illustrated versions had been published

4. (Day)dreams and Dystopias

“Alice in Wonderland provides us with the delicious question: what if we were dropped into our imaginary world but we were no longer pulling the strings?”

Abigail Davis, Why Alice is with us for the Long Haul

The appeal and popularity of dystopian fiction is evident in the recent YA craze (Hunger Games, Divergent, Maze Runner, to name a few). And there is a degree of the dystopian in Alice. Because dystopias don’t just present an awful world – they take a beautiful, brilliant, perfect ideal and twist and pervert it into an awful world. And arguably that’s what Carroll does: takes something we recognise, a child’s daydream, and lets loose the controls.

The 2010 Tim Burton film stresses this dystopian aspect, effectively asking: what would happen if we left Wonderland to decay?

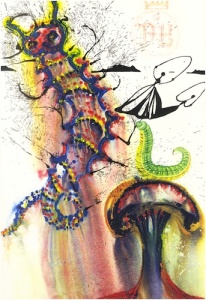

I recently discovered Salvador Dali’s illustration of Alice in Wonderland, prompting a further thought. Perhaps Alice represents not the controlled imaginings of daydreams but the unbridled craziness of our dreams. Like our dreams, and like surrealist paintings, it’s a distorted version of reality. It’s one in which Alice is both present, as the observer, and yet absent, as her conscious decision-making has no effect on the strange twists of Wonderland reality. Thus Wonderland is at once familiar and altogether unusual. In the same way that “garrumphing” is understandable subconsciously because it blends two things we recognise , we understand Alice subconsciously because part of us recognises our dream-state.

Sounds awfully Freudian, doesn’t it?

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrated by Salvador Dali.

5. Nostalgia for childhood

“Alice is tied into a kind of nostalgia … Even in Carroll’s time there were little shops set up in Oxford that would sell ‘Alice’ teacups and things like that.”

James Kincaid, Professor of English at USC

Nostalgia is powerful, whether it is remembering our childhood toys, memories, books or TV shows. And it is known for its power to prettify: that idyllic childhood home which is far smaller and creakier on revisiting; those funny stories so oft-repeated by family that they become memories even if we were too young to remember them. Reading the books we enjoyed as children will always prompt the pleasurable remembrance of those nighttime escapes.

6. Weirdness and Wackiness – the rabbit hole

” Alice is a text that doesn’t hesitate to do wildly playful things … with wild and wacky characters”

Elizabeth Tucker, Professor at Binghamton University in New York

Adam Tschorn of the LA Times points to the “’inherent weirdness’” of this “trippy text”. The appeal of escapism is indisputable – especially to the crazy world of Wonderland where none of the usual rules apply. And what better visualisation of escape than all those strange portals?

“Just as she said this, she noticed that one of the trees had a door leading right into it.”

Sci-fi/fantasy is the most popular genre for fans creating stories and artwork online. This is likely because, in the best of the fantasy genre, worlds are created which seem to have a life and momentum of their own, beyond the end of a book or film. Few people will go to the extent of tattooing Alice quotes on their skin in Klingon or Elvish (yes this has been done) – but the powerful attraction of exploring, discussing and sharing entire alternative universes is undeniable, whether it’s Roddenberry’s, Tolkien’s, or Carroll’s.

“Fantastic literature continuously challenges the reader’s (and the protagonist’s) sense of ‘the ground rules’ or what can be assumed.”

E.C. Constable, The Victorian Web

Fantasy doesn’t just explore other worlds, it also makes us question our own. Alice struggles to understand the rules of Wonderland, in the same way that many children (and adults) feel confused by the often-contradictory and seemingly nonsensical etiquette of the adult world.

Barry Moser’s bizarre illustration of the fish and frog footmen

7) Understanding Wonderland (or attempting to)

“Every joke should have a meaning”

Queen of Hearts

As the books are so bizarre, the range of interpretations is huge. And various adaptations layer on even more new meanings. Working out the whys and wherefores of such a weird world is intriguing. And we shape our readings to suit the age we live in – as one critic noted, “The ‘Alice’ books are just malleable enough to be read any way you want.”

In the 1960s hippie-heyday, the mushrooms the caterpillar offered were often seen as symbols for drugs

Thus in the 1940s it was Freudian dreams, in the 1960s it was drug-induced madness, and in the 1980s it was a paedophilic Dodgson’s desire for the real-world Alice. Arguably our current reading is post-modern. That there is no answer to almost all of Alice’s questions is curiously fitting to a generation which has grown up with a declining belief in divine explanations, unable to explain the horrors of the World Wars.

Numerous adaptations of Alice produce varying representations of the Queen of Hearts (the 2010 film blurring her character with that of the Red Queen) – with no single ‘canon’ interpretation

Regardless of broader interpretations, some more specific social jibes seem evident, such as in Carroll’s amusing depiction of Wonderland’s backward justice system, where the Queen “explains” that the Hatter is “‘in prison now, being punished: and the trial doesn’t even begin till next Wednesday: and of course the crime comes last of all.'” This could easily be a commentary on how jail and its social after-effects prompt further and more extreme crime, criticisms made explicitly in works like Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables.

Yet do most people really enjoy Alice for its Victorian social commentary? Do we really remember the nonsense of the Mad Hatter’s tea party because of its allusions to mathematician William Hamilton’s discovery of quarternions in 1843 (which Dr Melanie Bayley argues are its basis)?

Lewis Carroll himself mocked the seriousness with which readers studied the details of his books, sarcastically correcting pronunciations and definitions of the words in his poem The Jabberwocky.

I would argue it is the attempt to explain rather than the explanations themselves which fascinate us. That the nonsense medium is just as, or more, powerful than any political message hidden within it. That the question: “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” lasts far longer than the unsatisfying answer Carroll later gave: “Because it can produce a few notes, tho they are very flat; and it is never put with the wrong end in front!”

So why are we obsessed with Alice?

At one level it’s as unanswerable as Carroll’s riddle. But seeing as I’m already half-way down that rabbit hole…

Alice gives us the excuse to enjoy children’s books without being labelled childish. It justifies our enjoyment of the crazy and ridiculous by taking them to their extreme and making it ‘art’. Rather than simply nostalgically remembering our childhood, we reinhabitat it, in all its crazy daydreaming illogicity.

Carroll’s books produce a “thin place”, our very own rabbit hole to take us away from our world and into Wonderland, into our dreams or into our childhood. And there we find weirdness unmitigated by rationality. We find mysteries that cannot be solved, puzzles without proper answers, or at least, without answers that fit our ground rules on what ‘proper’ is. Alice in Wonderland, like its riddles, will remain fantastically curious. And that is precisely why we are so obsessed.

“These are not books for children. They are the only books in which we become children”

Virginia Woolf, on Alice in Wonderland

What is your opinion on Alice in Wonderland? Do you love it? Hate it?

Great post. It’s amazing how Alice has influenced modern culture. This was one of the first long chapter books I read to my son

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Doreen. I know, it’s crazy how widespread its influence is, even compared to other really popular books (children or adults). I think it was one of the first non-picture books my mum read to me! And because we all heard/read it as children it becomes this shared language where you can refer to, say, Tweedledum & Tweedledee and everyone knows what you’re talking about – there are very few other books I can think of which that applies to (Pride & Prejudice maybe?).

LikeLike

Good post, although a little too long for my taste. Have you seen Pan’s Labyrinth? The main character, the girl, travels through a tree into another world and her clothes mirror so much Alice’s ones in the Disney version (blue dress, white apron).

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by Patricia. Don’t worry, my next post will definitely be shorter! No I hadn’t heard of Pan’s Labyrinth actually, but I just watched the trailer online and it looks really interesting – will watch the full movie soon I hope! I loved one of the commentator’s descriptions – “unrelentingly imaginative” – that could well be applied to Alice.

LikeLike

Superb article, love it.

I’ve always had a fascination for the wacky, inexplicable, weird and slightly insane. What makes me love Alice in Wonderland is, I think, the fact that it is nonsense, it can’t be explained. It is just so strange, and just this particular shade of odd isn’t in any other book I have read at least.

LikeLike

Thank you – it’s my first one so I was very tentative in posting it!

I don’t think any other books I’ve read have been quite so strange either – although Coleridge’s Kubla Khan has definitely stuck in my mind for its (actually drug-induced) oddness – and no one has really managed to copy Carroll’s formula. Yes the inexplicable always has that mysterious draw, doesn’t it?

LikeLike

I love Alice in Wonderland! I think for me it’s something about the fantastical and how quickly her adventure changes…I also love the trippy aspect of it!

LikeLike

Good point there – the speed of the twists and changes in the book are really surprising. One moment they’re talking about things we recognise and the next it is completely bizarre!

LikeLike

I’m impressed, I must say. Really rarely do I encounter a blog that’s both educative and entertaining, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. Your idea is outstanding; the issue is something that not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I am very happy that I stumbled across this in my search for something relating to this.

LikeLike

I truly appreciate this forum.Really thank you! Cool. Maffia

LikeLike

I do not have any idea how I finished up here, but I

thought this post was great. I don’t know who you are but certainly you will be going

to a famous blogger when you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!

LikeLike

This can be a topic that’s near my heart… Cheers! Just

where are the contact information though?

LikeLike